For most locals, however, nothing less than the Pase de Cuarenta Visitas would do. To acquire it one had to travel to Algeciras and produce a receipt which proved that £8 had been changed officially in Spain at a ridiculously low rate of exchange. This Pase usually had to be renewed at the very least once a year and I collected quite a few all those years ago.

The third document was the Pase de Pernoctar which allowed people to stay overnight. All three documents were made of rather poor quality paper, each page perforated into a number of sections which were duly stamped and torn off by the Spanish officials as the visits progressed. The complete booklet was precariously stapled together inside a pink cover bearing the Spanish coat of arms with General Franco's ubiquitous motto, a reminder of the outcome of the Spanish Civil War.

¡España! ¡Una, Grande, y Libre!

To which the instinctive reply of all Gibraltarians - and indeed many a Spaniard was . . .

¡España! Ni Una, Ni Grande, Ni Libre!

The £8 receipt required for the forty visit pass also allowed local wits to come up with another crack at the motto.

¡España! ¡Una! Que si fueran dos, tendríamos que cambiar dieciséis libras.

On the inside of the cover was the inevitable photograph of the holder. It was not uncommon for these to be removed and replaced by those of other people who for one reason or another had forgotten to renew their passes. I was, I confess, a frequent offender - hence my opening comment.

So where did we go? Well mostly it was day trips to either La Línea or Algeciras - we ignored the ferry and travelled by car - but now and again we organised overnight stays in either Torremolinos or Marbella. In the latter we stayed at the best "pension" in town - The Jacaranda. It might be hard to believe but in those days there was only one hotel in the Costa - the Pez de Espada and that was just a bit too expensive for us..

Gibraltar and La Línea just before the Civil War began

Thinking back I doubt whether any other generation of young, more or less penniless Gibraltarians have ever had it so good as regards our very one-sided relationship with Spain. World War II had been traumatic for our parents. Our forced evacuation had taken its toll on them. But by the 195os we were all back home and coping.

This was not the case for Spainiards. Those who had left their country during their Civil War had been forced to do so - they were not evacuees - they were refugees. And unlike us by the end of their War many of those who had left would find it difficult - not to say incredibly dangerous - to return. The immediate aftermath of the "Nationalist's" victory left a country destroyed both physically and economically and a population damaged morally and psychologically.

Worst hit of all was the south. Traditionally the poorest and therefore the most pro-Republican, Franco and his rebel cronies had made sure that these people would pay for their perceived disloyalty. And La Línea seems to have ended up at the bottom of the pile. Before the Civil war it had been a fundamentally peasant society where the bulk of the population found themselves living in shabby poverty. It was a town held in thrall to its rich and powerful next door neighbour, increasingly dependent on it in order to survive - be it by finding work there or by smuggling (see LINK).

A decade or so on and there were hardly any noticeable changes anywhere along the Campo area or the nearby hinterland - other than an increase in the influx of tourists along the newly created Costa del Sol, of which the young female variety were always a welcome source of sport for most visiting. young, male Gibraltarians.

The yoke and arrows symbol of the fascist Falange were a common sight outside towns and public buildings throughout Franco's long regime

With the usual insensitivity of youth most of us made good use of our relative wealth and entertained ourselves accordingly. Our ignorance allowed us to disregard the many and insistent urchins that would surround us whenever we crossed the frontier on foot. We hardly ever gave them a penny - despite the fact that we often threw away the pitiful ten centimo pieces, so called coins that were actually made of cardboard with a thin metal covering - worthless to us but not to them.

Ten centimos - Una, Grande y Libre (1945)

It never seems to have occurred to me that there might be something fundamentally wrong with a world where one set of people could eat and sleep in somebody else's country in relative luxury for a whole weekend for a pittance - and still bring back plenty of change - whereas most of those that served and surrounded us could often hardly keep body and soul together.

A world where even the hungry were exploited is a world which most of us should reject. Instead just like many younger Gibraltarians I embraced it through apathy or ignorance and thanked a God that I really didn't believe in that I wasn't one of them.

When the Civil War erupted on Gibraltar's doorstep in 1936 the event was reported in the Gibraltar Directory with considerable coolness;

18th July 1936 - News received of military rising in Spain led by General Franco and other generals. General Queipo de Llano assumed power at Seville. Algeciras was taken over in a quiet manner. Disturbances in La Linea at night, fighting taking place in several streets and there were some casualties. Gibraltar residents who attended the fair passed through some anxious moments until their safe return to the Rock.

It was indeed an unfortunate coincident that the very popular La Línea annual fair was taking place on the day the fighting actually started. As always during Feria time the place was full of visiting Gibraltarians. The population of La Línea who as I have already mentioned mostly sympathised with the Republic Government, so it was not at all surprising that the arrival of Franco's "Moorish" troops quickly led to a series of ugly clashes between government sympathisers and fascists.

The Gibraltarians who had just a short while ago been enjoying themselves at the fair suddenly developed an urgent desire to return to the Rock. They were joined by a couple of thousand of their compatriots who lived in La Línea all the year round as well as quite a few other thoroughly frightened Spaniards of every political hue.

The Gordon Highlanders and others trying to cope with the influx of refugees at the frontier in North Front - note barbed wire and wooden planks ( 1936 )

This is how Joe Robeson - an old school friend still living in Gibraltar at the time of writing - describes what happened when the Civil War spilled over and on to Gibraltar's doorsteps:

The story as told to me by my father was that the Spanish Civil War . . started on what was/is the traditional start of the La Linea Fair. Franco - one of several leaders of the Nationalists - brought his Moroccan Troops over to Algeciras and worked his way to La Línea. They were temporarily stopped by a couple of sergeants of the Spanish army with a machine gun on top of the flat crenulated roof of their barracks, which . . . was just outside the Aduana on the bay side.

They did so until their ammunition run out when they escaped and joined the many people including many Gibraltarians my father and his mates included, running along the beach towards Gibraltar with bullets flying over their heads.

That night the soldiers at the barracks in La Línea mutinied and imprisoned their officers. According to a Times correspondent the number of refugees was in the region of from 4 to 5000. Under the heading of "Moroccan Troops at La Línea" he wrote:

Refugee British residents from La Línea are pouring into Gibraltar, which is crowded with refugees, many sleeping in parks and open spaces . . . A local shipping firm, Messrs M.H.Bland and Co has placed at the disposal of the refugees a large shed on the waterfront which is packed with women and children . . .

"Moorish" guard at the Spanish frontier in 1936 with a rather self satisfied fellow behind him.

When the Moroccans arrived the troops pretended to be unarmed, but the Moroccans on entering the barracks were fired on from above and two were killed and many wounded. The exact number of casualties is unknown but is believed to exceed fifty. Two British subjects, Edward Marshall and Mr. Ellicott were also wounded in the hands of (sic) stray bullets . . . .

San Roque and La Línea are occupied by well-equipped Moroccan troops. As a result of snipping by armed civilians at La Línea last night the troops retorted with a continuous fusillade, causing many casualties especially in the district of the La Línea Infantry Barracks. A large crowd watched from the British frontier what can only be described as a miniature battle. . .

In other words a rather unsympathetic report full of weasel words - snipers on the one hand, well-equipped Moroccan on the other - one almost gets the impression that the whole civil war might have been avoided if those pesky people hiding in the Infantry Barracks hadn't decided to defend themselves.

Several members of my own family (see LINK) were caught up in the fracas. My mother's cousin Mercedita Wills and her son Maurice - for example - were staying in San Roque that Saturday. Hearing an almighty racket outside the pension where they were staying, young Maurice opened the window of their room to find out what was happening. When his mother joined him she found herself staring at a dozen rifles held by an uncompromising squad of "Moorish" troops.

'Close the window madam. Don't you realise that we are at war?'

Luckily for Maurice and his mum the officer in charge had decided not to order his men to open fire. My grandmother’s sister, Carmen Vacca was also in Spain spending the summer in her family´s property in La Línea. There are memories of her turning up in hysterics at our house in 256 Main Street just after the shooting had started

The Directory continues:

19th July 1936 - La Línea fighting continues; several officers fled into Gibraltar this morning. By noon La Línea had been taken over. In the evening heavy firing was heard which was due to the officer commanding the Moorish regular troops being killed by a civilian. Many casualties caused when the troops retaliated. Several wounded brought to the Colonial Hospital . . including the Marquez de Povar and Garcia Delgado, who was riddled with bullet holes and succumbed to his wounds. Telephone and telegraphic communication with Spain cut off. Refugees commence to arrive at Gibraltar.

20th July 1936 - More refugees arrive from La Linea and neighbourhood. British subjects in Marbella brought over by the British tug "Noel Birch"

The Glasgow Herald (1936 )

There were so many refugees desperately trying to get out of Spain that the local fire brigade were called in to control the crowds using water hoses.

Many of the refugees took up residence in some of the hulks in the harbour or in overcrowded slums. Some hid in caves.

Several Gibraltar hulks anchored in the Bay (Pre-Civil War photo)

Meanwhile refugee camps and soup kitchens were set up in North Front. Tourist traffic came to a complete halt. There was a steady stream of fishing boats from la Atunara on the east coast ferrying people to Catalan Bay.

21st July 1936 . . . dockyard tug "Enegetic" brings 130 British and Spanish refugees from Algeciras. Gibraltar Chronicle issued special English and Spanish editions . . .

The Gibraltar dockyard tug Energetic - it belonged to the local company - M.H.Bland and Co (See LINK)

A Spanish edition of Gibraltar Chronicle - 21st July 1936

Carabineros seeking refuge (1936 )

Refugees from the Campo area seeking refuge in Gibraltar (1936 )

Probably the calm after the initial storm (With thanks to Andrew Schembri )

Despite allowing people to find refuge in Gibraltar, the British authorities in Gibraltar proclaimed a theoretically strict neutrality throughout yet invariable took actions that aided one side to the detriment of the other. Although difficult to prove I have often wondered whether the reason the authorities acted with such equanimity was because they found it difficult to distinguish between Gibraltarians who happened to live in La Linea and were legitimately entitled to return to Gibraltar whenever they pleased, and those who were Spanish nationals seeking refuge.

Refugees arriving by boat

As they saw it the Republicans equated with Communism, anarchy, anti-imperialism and a serious lack of law and order, whereas the Nationalists were a safeguard against precisely these philosophies - every one of which they considered unacceptable. In Franco's own words, his was a Spain that would become

. . . la reserva espiritual del occidente . . . y el baluarte contra el comunismo.

That the Republican Government of Spain was at least based on democratic principles whereas the Nationalists were unapologetically founded on dictatorial ones seems not to have made much difference to Britain. And it was more or less the same in Gibraltar - a lot of patting of local backs about our generosity - or should I say the British administration's - towards these unfortunate people. But the real story is far more complex than that.

The Gibraltar Chronicle, (see LINK) for example, made no bones about calling the Republicans 'Reds' whereas the insurgents and rebels were touted as Nationalists. Its opinions, in so far as they reflected those of ordinary people, however, were rather irrelevant as it was not a civilian Gibraltarian newspaper, but very much the mouthpiece of the Colonial establishment.

The working-class in general and Union members in particular were just as likely to lean towards the left as the wealthier trading class and the clergy were towards the right. On the otherhand, Freemasons who were on the whole pretty well off individuals and of which there quite a few in Gibraltar, were hardly likely to favour Franco who was known to have a paranoid hatred of the society

Milk being distributed to children

Refugees given medical attention

In the stagnant atmosphere of a fortress colony, civilian politics rarely rose above the parish pump level. People tended to be politically uninformed and opinions were bandied about in ignorance of the issues involved. Generally speaking, however, a majority of the population were probably more in sympathy with the insurgents than with the Republican cause. The decision by the Fascist powers - Germany and Italy - to help the "Nationalists" probably made little difference to their overall opinions. There were I suspect, several reasons why this was so.

As a largely religious community, Gibraltarians were influenced by rebel propaganda which labelled their uprising as a crusade in defence of religion, and made capital of the violent anti-clerical activities of extreme elements within the Republic. It was only with hindsight that the full horrors of Fascism and Nazism became clear.

Nor would the British or the better-off Gibraltarians have been too enamoured with the Republic Government when it forbad any new purchases of property in the Campo area by Gibraltar residents. The Spaniards were quite reasonably afraid of further encroachment by Britain under the excuse of protecting British property. Later the non-interventionist policies of the Western Democracies - and in particular that of Britain - must also have had a strong influence on Gibraltarian public opinion.

It retrospect it has become increasingly obvious that while the British Government under Stanley Baldwin adopted a neutral position during the conflict and promoted the so called Non-Intervention Committee, they were always discretely willing to give the Nationalist a helping hand. Gibraltar consistently refused to fuel or give any assistance to ships of the legitimate Republican fleet that patrolled the Straits of Gibraltar yet was more than willing to sell supplies to both Seville and Cadiz both in the hands of the insurgents.

When Neville Chamberlain - whose first name I was given by my family two years later because they thought he had brought "peace for our time" - succeeded Baldwin as Prime Minister, he made no effort to change the government's policy. The British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden was publicly in favour of the official policy of non-intervention. Privately he was hoping for a rebel victory.

The British First Sea Lord - Admiral Lord Chatfield - admired Franco to such an extent that he managed to get the Royal Navy to openly favour the rebel's cause - and the following gives us a clue as the reason why. A quote in a 1936 Report of Proceedings of the Royal Navy attributed to the officers of a British destroyer contrasted . . .

(Republican) gangs of proleterians invested with the authority of a rifle and pistol and little inteligence . . . (with) delightful (National officials) imbued with that charm of manner for which the Spanish gentleman has long been famous.

Admiral Lord Chatfield

During the conflict, the German warship Admiral Scheer visited Gibraltar. This pocket battleship formed part of the International Control naval units set up during the Spanish Civil War by the European powers as a coastal control system to discourage the entry of foreign combatants.

These ships showed their neutrality by having red, white and black strips painted on their forward gun turrets. The inclusion of German ships in these units helped Germany maintain the façade that their military aid to Franco was made up of volunteers. My mother Evelyn Chipulina was always very impressed by the formal politeness of the German mariners whenever they happened to enter the family "Art Shop" in Main Street with much saluting and clicking of heels.

The Admiral Scheer in Gibraltar - The colours of the strips on her front turret were those used by the International Control naval units - The building on the right was the Royal Navy Headquarters in the Dockyard

As well as permitting Franco to set up a signals base in Gibraltar, the British authorities also provided information on Republican shipping to the Nationalists. Direct intervention in the formidable shape of HMS Queen Elizabeth was used to prevent the Republican navy shelling the port of Algeciras.

HMS Queen Elizabeth anchored at the South Mole

On more than one occasions this lack of impartiality - not just by the British but by some of the more prosperous merchants in Gibraltar during the Civil War - had a direct effect on the outcome of particular battles. On the 21st of July two Spanish heavy cruisers and a destroyer entered Gibraltar harbour during the night requesting fuel. On the orders of the Republican Government the sailors had overpowered their officers and taken over the ships.

The Royal Navy refused to give them any fuel but was willing to allow local merchants to supply them. A local, Lionel Imossi, acting on behalf of the coal merchants (see LINK) told the Spanish Consul that his colleagues would supply the coal if the sailors released the officers. On being told that there were no officers aboard, the gentleman replied that in that case they had nothing to sell. On that same day La Línea was bombed again by the rebels.

The Gibraltar Directory continues:

22nd July 1936 - Spanish Government war vessels arrived at Puente Mayorga, Gibraltar Bay. They were attacked by Nationalist planes and a combat ensued, pieces of shrapnel falling on roof of the Rock Hotel and at Catalan Bay. Suitable warning sent by H.E. the acting Governor, Brig the Hon W.T. Brooks, to both sides. Subscriptions opened for destitute refugees. Civilian volunteers assist police.

Something like nine months later the authorities decided that it would be safe to appoint a local man - Lionel Imossi - as commandant 0f the volunteers, - the same man who had represented the coal merchants previously - and a man obviously to be trusted.

Lionel stood for re-election to the council in 1936 and suffered strong attacks from working class Gibraltarians, perhaps as a result of his open obstruction to the Republican flotilla re-fuelling in Gibraltar a few months before. One union man declared that Imossi was :

He was also accused of trying to monopolise tobacco smuggling by paying for the collaboration of the Spanish Customs.

Lionel’s wedding reception party taken on the balcony of Arengo’s Palace - Bishop Fitzgerald is flanked by - I think - Imossi on the right and his new wife Victoria nee Sacarello on the left - Curiously I am distantly related to Victoria since her father and my grandmother Memo Sacarello were siblings. I hasten to add that I never knew her (Unknown)

Another local who covered himself in glory was a lawyer for his own family business, one of the richest in town. He also stood for re-election to the City Council in 1936 on a Chamber of Commerce ticket. During the hustings he was accused of exploiting his workers. A heckler called him 'El Bandido' and also accused him of trying to monopolise tobacco smuggling by paying bribes for the collaboration of the Spanish Customs.

More to the point, when refugees were evicted from the Exchange building at the start of the Civil War, he was reminded at a public meeting that had helped the Spanish authorities financially and yet could not spare a single penny for his fellow citizens who were at the Exchange and were in desperate need of help.

On the 23rd of July while 1200 refugees were being housed under canvas in the North Front the Rebel Colonel, later General Kindelán (spelt Kinderlin in official British documents), called on the authorities in Gibraltar and apologised for the trouble caused by his planes. Apologies not only accepted but friendships made. Later on during the conflict and with the full permission and blessing of the British authorities, Kindelán made use of Gibraltar's telephone exchange to contact and make suitable arrangements with both Italy and Germany.

Postcard showing refugees entering the rock and the setting up of a tented village to house some of them in North Front (1936 )

Refugees housed in military tents in North Front

"Tents in North Front" is a phrase that Gibraltarians tend to associates with Spanish Civil War refugees but as previously mentioned, quite a few others were either given or found shelter elsewhere. And some were also housed in the Windmill Hill Detention Centre - although it is hard to determine here whether the word "refugees" still applied.

The original captions reads - "Spanish refugees under the supervision of a Gibraltarian officer"

The original caption reads

"12th August 1936; Carabiniers, Customs Officials and airman of the Spanish Government interned in the Military Detention Barracks at Windmill Hill, after Moorish troops arrived in Spain" !

25th July 1936 - Government notice published as to resumption of normal conditions of entry and residence in fortress; visitors warned to leave Gibraltar owing to serious shortage of accommodation.

Almost at the same time as this, bland and relatively reassuring notice was made public, Spanish Government planes were pounding away at Algeciras, La Línea and San Roque. On the 29th of July a hostel was opened at St Mary's Catholic School to house British refugees. Meanwhile rebel planes continued their attacks on Government shipping sailing close to Catalan Bay.

Happier days at the frontier - An odd photograph as I have not been able to find out who the fellow beside the young lad is. (1931)

Time passed, but the effects of the Civil War continued to cast a shadow over events on the Rock. Although the airstrip in Gibraltar will forever be associated with World War II its origins lie within the timescale of the Spanish Civil War. Work began on a grass strip on 3rd September 1934 south of the 1909 fence. It was completed in March 1936, all for a total cost of £573.

The grass airstrip on the old race course -

In August 1936 two shells fell at Eastern Beach and Race Course, (see LINK) luckily causing no damage

In Spain General Queipo de Llano was now Franco's top man in Andalucia. His nightly broadcasts from Radio Sevilla would constantly refer to the Prime minister, Manuel Azaña, who was allegedly gay, as Doña Manolita. He became notorious for his brutal exhortations.

"Si encontráis un rojo, pegarle un tiro en la nuca; y si no seis capaz, mandármelo a mi, que yo se lo pego."

And his threats :

"Los buscaremos hasta los fines de la tierra y si están muertos los volveremos a matar."

The above are almost certainly apocryphal but I have no doubt that his broadcasts must have sent shivers down the spines of the refugees crowding North Front as he ranted and raved about the retribution his troops would inflict on them. This charming character once turned up in La Línea and ordered all refugees still in Gibraltar to return to Spain and work for the salvation of their country instead of patronising the local bars looking at the legs of dancing girls. It was from here that he made his much publicised threat that he would soon be riding up Main Street to Government House on a white charger.

General Gonzalo Queipo de Llano

The bars that catered mostly for visiting naval seamen were probably far too expensive for the refugees to indulge in "looking at the legs of dancing girls" (1954 - Bert Hardy ) (See LINK) In 1938 the Daily Herald reported that a number of

Gibraltarian fascists had attended a Campo de Gibraltar rally which was addressed

by Queipo de Llano. According to a telegram from the Secretary of State for the

Colonies to the Governor of the Rock, among those cheering in the crowd was a member

of Gibraltar’s well-known merchant families.

During the last days of the Civil War this gentleman together

with several other of his rich merchant friends - including the well-known benefactor who gave

his name to Gibraltar’s main square - sent lorry loads of food to Madrid to assist the rebels forces who had just

entered the City.

Meanwhile, in Gibraltar, a local bakery owner by the name of Amar, opened his house to many of the refugees. Far from patronising the local bars, these people would dearly have loved to return to their homeland but were too frightened to do so. Eventually the place became a sort of transit camp as more and more refugees took advantage of his hospitality.

Amar was a merchant and no political activist. No doubt he sympathised with the Republic, but his was certainly a humanitarian gesture. When he died many years later, his funeral had a massive cortège of grateful people from La Linea.

On the 5th of August 1936 on a heavy levanter day, the Government destroyer Lepanto was hit by a bomb and entered Gibraltar harbour. The British confirmed their neutrality by ordering it to leave or risk being interned. The ship moved out.

The Republican Destroyer Lepanto

The original caption reads - 'Agosto 1936. Un marino español es socorrido por marinos britanicos . . .

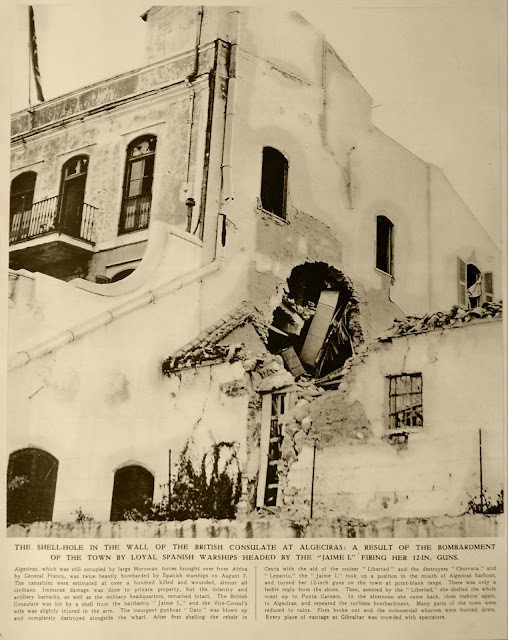

Also in August 1936 Spanish republican warships bombarded rebel-held towns in the Campo area. Many of the refugees in Gibraltar - many of whom came from Algeciras which bore the brunt of the attack - had a depressingly good view of the entire event. As did the Governor of Gibraltar, General Sir Charles Harington (see LINK) who left us this record of his experience:

I witnessed the Government battleship Jaime I steam slowly past Algeciras, within a mile of it, and fire its broadsides into that undefended town. The first shell hit the house of the British Vice Consul; he and his wife had a very narrow escape.

Refugees and Gibraltarians watch the Jaime I bombarding Algeciras - I think the date is more likely to have been the 7th of August but I am not entirely sure (Getty Images)

Spanish Republican warships ready to bombard Algeciras - which is what the refugees and Gibraltarians in the previous photo were watching

The destruction of the Cafe Bar Casero in Algeciras by Republican ships

But that is not the entire story.

Soon after the three republican shipsthe Jaime I, the Libertad and the Miguel de Cervantes had arrived and had anchored in the Bay, British boarding officers visited the Libertad and asked to see Commander Fernando Navarro Capdevilla who was supposed to be in charge of the cruiser. After a very long wait, an unshaven, smelly individual wearing a very crumpled uniform of a Capitán de Fragata, came up on deck to meet them. He was very noticeably not wearing any socks.

The British officers’ worst fears were confirmed. The fellow was impersonating his commanding officer that he and his co-mutineers had undoubtedly killed. It was the kind of behaviour one might expect of anybody associated with communism. In fact what had actually happened was that all three ships had run out of water for several days and there simply wasn’t enough of the stuff for anybody to wash themselves - let alone their clothes.

On the 7th of August, the three ships moved west, the Jaime I bombarded Algeciras and the Libertad shelled the coastal batteries at Punta Carnero. The Miguel de Cervantes does not seem to have played a part in all of this.

Incidentally, nobody had laid a finger on Commander Fernando Navarro Capdevilla. He had been retired from active service by the government and was posted as a naval attache to the Spanish Ambasador in London. As I will explain later, it was he who would later arange for the destroyer José Luis Díez to return to active service with the Republican fleet.

Curiously although any number of photographs were taken of the effects of the attack on the town hardly any exist which depict the ships actually carrying out the bombardment, The photo held by Getty Images which is supposed to have been taken on that day, actually turns its back on Algeciras and looks towards the Rock.

One way or another, the Civil War touched everybody in Gibraltar either directly or indirectly. Just next door to 256 Main Street - where my family lived at the time - there was a fruit shop called Perez & Navarro. The family were regular customers. One of the partners, I cannot remember which one - had an unpleasant time during this period, although he had never been involved in politics.

Main Street in the 1950s with George's Lane on the right - 256 Main Street is - or was as it no longer exists - the narrow two storied house to the right of the glass covered balcony. Perez & Navarro was just to the left of it (1954 - Bert Hardy )

At the outbreak of the conflict he had happened to be a member of a social club in La Línea where he would often relax with friends over a few drinks and perhaps a game of dominoes or chess. Club members, however, tended to be left-wing sympathizers and when the fascists took over he fell under suspicion. They never actually accused him of anything but they never left him in peace.

A Spanish seaplane forced to land in Gibraltar waters after having its engine damaged by gunfire from Algeciras ( Thanks to Yolanda Pilkington )

Meanwhile Governor Harrington made no bones about his o0wn political leanings. An admirer of General Franco he wrote to his opposite number in Algeciras asking him if it might be possible for the Royal Calpe Hunt (see LINK) to meet again. The admiration must have been mutual as Franco wrote back to him directly and in English albeit rather ungrammatically.

I am glad to give you these good news (sic) and to assure you at all times of my good will, but you will undoubtedly understand. I should like to fix up the route with you beforehand so as to avoid the War Zone.

Harington on the extreme right with other members of the Royal Calpe Hunt in Spain - The ladies will almost certainly have been wives of very well-off teratenientes of the Campo de Gibraltar area who had supported the uprising (1934)

The fellow to the left of Harington with his hand in his tummy is Pablo Larios, Marques de Marzales and Master of the Royal Gibraltar Hunt. His daughter Natalia may very well be at the back of that lot in the background.

During the early 20th century Natalia – known to all as Talia - became an ardent follower of the Calpe Hunt. As a beautiful lady and an exceptional horsewoman she became extremely popular with the officers of the Garrison. As late as the early 1940s the Governor, Viscount Gort, was absolutely besotted with her.

Talia, Marquesa de Povar

Talia married the Marquez of Povar who managed to get himself shot in La Línea while defending the local Barracks from a counterattack by Government forces. His wife got him into the Colonial Hospital in Gibraltar while she established herself in a flat in College Lane.

When the rebel air force General Kindelán visited Gibraltar in 1936, ostensibly to apologise for damage caused by Nationalist planes but actually in order to make a series of crucially important international telephone calls, it was Talia who made the opening introductions to the British authorities.

Alfredo Kindelán - Is it my imagination or does this fellow bear a marked resemblance to a well-known war-time German Chancellor?

By 1937 the DSO (Defence Security Officer) in Gibraltar had opened a file on her. She held a Nationalist passport issued in Cadiz in 1937 and was working openly for Franco’s Intelligence Service.

In the middle of all this the official line continued to hold;

10th August 1936 - Special warning issued that British Government's attitude in regard to Spanish Civil War is one of strict neutrality and calling on the inhabitants to refrain from speaking or acting with partiality to any of the contending parties.

Later General Harington recalled in his memoirs:

I could not help being amused when, in the midst of my definite warnings that the policy of the British Government was one of strict neutrality, a man came into my office carrying the fragments of a bomb which had been picked up in a field near San Roque; it had a steel label attached to it bearing the name of a firm in Shepherd's Bush! I had tremendous satisfaction in sending that label direct to the C.I.G.S

General Harington taking the salute outside the Convent - he may have been an uncritical admirer of the Generalisimo but as shown in his memoirs he did have a sense of humour (1936 )

13th September 1936 - £98-7-9 and Pts 4446 raised to date for the Poor Refugee Fund; in addition many gifts in kind were made. Disturbances at Irish town in connection with the closing of the refugee Camp; several arrests made on charges of assaulting the Chief of Police and other police officers.

An interesting entry. The amount was a relatively paltry one - about £6000 in today's money - especially when taking into account the number of people involved. But far more interesting is the juxtapositioning of charitable activity with the unacceptable actions of those receiving it. It is also now quite clear that the refugees were becoming a problem - the solution of which incidentally is never made all that clear in any subsequent official entries. At any rate I can't find them.

At least one source suggests that perhaps well over half the refugees that entered Gibraltar in the summer of 1936 were actually Gibraltarians who resided in the Campo area, a corollary of which was the extent to which the Campo area had been shouldering a very large portion of Gibraltar's perennial housing shortages.

General Harrington had in fact long been warned by his Senior Medical and Staff Officers about the possible danger of an epidemic. Gibraltar, they argued, was living on a volcano. They urged him to make the refugees - both those who were Spanish as well as British subjects - return to La Linea . . . and by force if necessary. In many cases this would have meant certain death.

The market area - note barbed wire surounding the small building presumably to deter people from entering and using it as a refuge

Nevertheless during December 1936 and January of the next year the British destroyers HMS Gypsy, Gallant and Achilles were given the task of returning nearly 700 refugees, mostly men but also a number of women and children, back to ether Republican or rebel-held ports.

The Civil War continued to dominate events in Gibraltar throughout 1937. In May the German pocket battleship Deutschland, was hit by bombs off Ibiza and entered Gibraltar harbour. Like the Admiral Scheer the Deutschland formed part of the International Control naval units which had been set up by the European powers. The ship had been caught napping in Ibiza with its sailors lolling about, sunbathing on deck. Their anti-aircraft guns never managed a single retaliatory shot and to make matters worse, they were unable to get to their medical supplies as the doors were jammed - so much for the stereotype of German efficiency.

Deutschland casualties, visitors and British medical staff at the Royal Naval Hospital in Gibraltar (1937 - Thanks to Yolanda Pikinton)

All told some 26 German sailors died, 9 of them of injuries in the hospital in Gibraltar.

The funeral cortege of the German sailors of the Deutschland

on their way to the cemetery at North Front - note two locals giving the Nazi

salute in the last photograph ( 1937 - Photos obtained from Andrew Schembri and

Jason Mesilio )

Those two Nazi saluting individuals have reminded me to mention that there were actually two Fascist organisations in Gibraltar at the time. One was led by Hunberto Figueras who identified the group with the Spanish Falange. The other was led by Luis Bertuchi, an admirer of Mussolini. Unfortunately that is about all that I know about these people - other than that they had quite a few supporters.

The Deutschland then sailed away into the sunset while Germany withdrew from the International Control - although not before shelling the still Republican port of Almeria.

The Deutschland before she joined the International control units (1936)

By a coincidence, the British Gibraltar based destroyer HMS Hunter, which was also part of the International Control, hit a mine at about the same time as the Deutschland incident with 8 men killed and 9 Injured.

A badly damaged HMS Hunter back in Gibraltar

My brother Eric witnessed the funeral cortege of both sets of casualties. The former was followed by a handful of people, mostly made up of British military and civilian officials. The latter, according to Eric, was a procession of what seemed to be the entire dockyard workforce. The Hunter funeral was covered by M.A. Benyunes, a Gibraltarian photographer.

Comment on the back of one of the photographs

On the whole I would say that my brother had not been exaggerating in his description of the funeral.

Meanwhile the city of Malaga, was in effervescence. There were innumerable strikes and boycotts and the "Hammer" and "Sickle" was plastered on every wall. The most popular slogans were 'Long live Russia!' and 'Down with Spain!' The "peasants" were in revolt, burning churches and farms, but every effort seems to have been made not to molest foreigners. At the time of the coup, the city was under the control of workers' syndicates and a number of priests and right-wing elements were killed. This, together with the growing disorder, filled the upper and middle classes with panic and many tried to leave the city.

The road to and from Gibraltar was soon closed, but Malaga could still be reached by sea. As the Captain of the Gibraltar based destroyer HMS Vanoc wrote many years later:

Lying off the Spanish ports we would hear splashing in the darkness as desperate men swam out to us from the shore. For many it was their last hope. They were under sentence of death.

At the time, my father Pepe Chipulina was friendly with a Royal Navy postman who often visited his Art Shop in Main Street and from whom he got first-hand accounts about HMS Vanoc. The destroyer had apparently logged some 17 000 miles in one year as she shuttled people in fear of their lives from one Spanish Zone to another - not just Nationalist sympathisers from Malaga but Republicans caught out in the wrong places at the wrong time.

HMS Vanoc

A friend of the family who was married to a Spaniard was unfortunate enough to be living in Malaga at the time. Apparently the family had servants who happened to be anarchist informers. Luckily they reported to their bosses that their employers had never discussed politics in their hearing. One can almost hear the sigh of relief. When the Rebels finally entered Malaga, they took a frightful revenge, executing 4000 people during their first week in charge.

By the beginning of May 1937 more refugees were continuing to arrive Gibraltar and on the whole the local British authorities appear to hjave been reluctant to send them back via the frontier at La Línea. Despite Spanish assurances La Prensa de Buenos Aires reported that 45 prisoners had been killed the previous month after being forced to work on new fortifications along the road from Algeciras to Tarifa.

In August 1937 Admiral Rolf Carls arrived on board the Scheer on an official call to express the German Government's thanks for the treatment of the Deutschland and its dead and wounded. Indeed he was actually here on behalf of the Führer, Adolph Hitler. Harington invited the Admiral to a luncheon party at the Convent and in the evening allowed himself to be his guest of honour aboard the pocket battleship. The next day it was more of the same with the local German consul, G.F. Imossi in attendance.

Somewhat insensitively Governor Harington allowed himself to be invited aboard the Deutschland

Perhaps even more insensitively members of HMS Hood played a football friendly against those of the Deutschland in the old Naval Ground

By the end of the year the war was taking a back seat as most of the action was in the north as the rebels slowly advanced on Madrid, Barcelona and elsewhere. Meanwhile in the south Harington would have been pleased to notice that his predilection for law and order was more than ensured by the Nationalist's deployment of large contingents of all types of policemen and para-military corps such as the Guardia Civil.

Los Guardia Civiles

In August 1938 the war became hot news on the Rock once again - the Republican destroyer José Luis Diez limped into Gibraltar harbour with a gaping hole in her bows, the result of a battle in the Straits with Nationalist warship - an event that coincided with Sir Edmund Ironside taking over as Governor. It was he who was responsible for the building of Gibraltar's ARP shelters which were destined to become eyesores for years to come. Unlike his shelters he only lasted a year.

General Edmund Ironside's shelters mostly under John Mackintosh Square - I think they are still there at the time of writing

A few months before her appearance at Gibraltar, the José Luis Diez - captained by Juan Antonio Castro Izaguirre - had escaped to England to avoid capture. When she sailed south to re-enter the war she did so painted with the pennant number of HMS Grenville and flying the Royal Navy flag. Her captain thought it would give him a better chance of sailing her through the Straits by doing this.

José Luis Diez flying a white a White Ensign

The dockyard was unable to undertake repairs because of the non-intervention pact, but the ship's crew undertook the task themselves. She was moored close to the shore and it was possible to see the damage from the Boulevard.

The damaged José Luis Diez in Gibraltar Harbour. The destroyer had long been a feature in waters surrounding Gibraltar - to such an extent that the locals dubbed her Pepe, el del puerto

Officers of the José Luis Diez - the captain - Juan Antonio Castro Izaguirre - is second from the right

On New Year's Eve the José Luis Diez tried to break out but was quickly accosted by rebel warships. She managed to round Europa point but was driven towards the shore by enemy gunfire just in front of Catalan Bay. (See LINK) Several Caleteños were hurt by Insurgent shell fire.

The story goes that the reason the rebels were ready for her was because they were alerted by the firing of several rockets from the Royal Gibraltar Yacht Club. Quite a few fingers have pointed at the Marquesa de Povar accusing her of having fired those rockets. I think it far more likely that she had somebody do it for her. That would have certainly been far more her style.

The José Luis Diez - Eventually her captain ran her aground hoping to stop her capture by the insurgents - He was wasting his time - The British refloated her and handed her over to the rebels

Damage to a Catalan Bay house caused by Rebel warships

The Stagno family - owners of the damaged Catalan Bay house - lodged a claim for injuries and damages against the Franco regime at the end of the Civil War. As expected they never received a single penny in compensation. PC Joseph Baglietto was also injured by shrapnel. He didn't get a penny either.

Catalan Bay - The José Luis Diez being refloated by Gibraltar harbour tugs one of them beieng the Energetic - note again the damaged roof of houses in Catalan Bay

The original caption reads : "Spanish sailors detained. Sailors from the Spanish warship Jose Luis Diez which went aground under the shelling of rebel warships and shore batteries when she tried to leave Gibraltar, are shown being taken to the detention barracks at Gibraltar."

So much for neutrality! Although I suspect that the bit about shelling from the "shore batteries" is incorrect.

Talia stayed in Gibraltar for the duration of the Civil War and the new Governor General Gort fell heavily for her charms - despite the fact that she was known to be working for Franco’s Intelligence service and was openly pro-Hitler. The photograph below was taken in 1941, the Civil War was done and dusted and Britain was up to its neck in WWII problems They were certainly not winning it.

Guests of the Governor Lord Gort walking the walk at in the gardens of the Convent - From left, General Barron y Ortiz, Governor

of Algeciras, the Marquesa de Povar, the Duke of Gloucester - a son of George V and liason officer to Lord Gort in France - and Señora Barron

The next governor of Gibraltar was Frank Noel

Mason-Macfarlane. He was usually known as Mason-Mac. He was a Labour party supporter but is best known to the locals as the man who dismantled the Devil’s Tower for specious reasons - He soon put a stop to all this Talia nonsense when he took over in 1942.

Throughout the 1950s and beyond my young friends and I continued to enjoy our privileged position among our Campo neighbours - as many others would do for many years after the end of the Spanish Civil War.

What can I say!

Somewhere between La Linea and Algeciras - for them Gibraltar was an unobtainable mirage in the distance.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)